–

63 KB – 32 Pages

PAGE – 1 ============

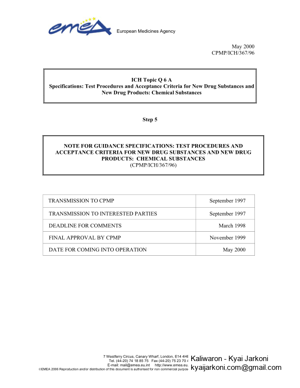

European Medicines Agency 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 85 75 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 40 E-mail: mail@emea.eu.int http://www.emea.eu.int EMEA 2006 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is au thorised for non commercial pur poses only provided the EMEA is acknowledged May 2000 CPMP/ICH/367/96 ICH Topic Q 6 A Specifications: Test Procedures and Accepta nce Criteria for New Drug Substances and New Drug Products: Chemical Substances Step 5 NOTE FOR GUIDANCE SPECIFICATIONS: TEST PROCEDURES AND ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA FOR NEW DRUG SUBSTANCES AND NEW DRUG PRODUCTS: CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES (CPMP/ICH/367/96) TRANSMISSION TO CPMP September 1997 TRANSMISSION TO INTERESTED PARTIES September 1997 DEADLINE FOR COMMENTS March 1998 FINAL APPROVAL BY CPMP November 1999 DATE FOR COMING INTO OPERATION May 2000

PAGE – 2 ============

© EMEA 2006 2 SPECIFICATIONS: TEST PROCEDURES AND ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA FOR NEW DRUG SUBSTANCES AND NEW DRUG PRODUCTS: CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES TABLE OF CONTENTS TRANSMISSION TO INTERESTED PARTIES..1 1. INTRODUCTION3 1.1 OBJECTIVE OF THE GUIDELINE .3 1.2 BACKGROUND .3 1.3 SCOPE OF THE GUIDELINE ..3 2. GENERAL CONCEPTS..4 2.1. P ERIODIC OR SKIP TESTING 4 2.2. RELEASE VS . SHELF -LIFE ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA ..4 2.3 IN-PROCESS TESTS .5 2.4. DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT CONSIDERATIONS 5 2.5. LIMITED DATA AVAILABLE AT FILING ..5 2.6 PARAMETRIC RELEASE 5 2.7 ALTERNATIVE PROCEDURES .6 2.8 PHARMACOPOEIAL TESTS AND ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA ..6 2.9 EVOLVING TECHNOLOGIES 6 2.10 IMPACT OF DRUG SUBSTANCE ON DRUG PRODUCT SPECIFICATIONS ..7 2.11 REFERENCE STANDARD .7 3. GUIDELINES7 3.1 SPECIFICATIONS : DEFINITION AND JUSTIFICATION 7 3.1.1. DEFINITION OF SPECIFICATIONS ..7 3.1.2. JUSTIFICATION OF SPECIFICATIONS 7 3.2 UNIVERSAL TESTS /CRITERIA 8 3.2.1. NEW DRUG SUBSTANCES 8 3.2.2. NEW DRUG PRODUCTS .9 3.3 SPECIFIC TESTS /CRITERIA.10 3.3.1. NEW DRUG SUBSTANCES .10 3.3.2. NEW DRUG PRODUCTS ..12 4. GLOSSARY (THE FOLLOWING DEFINITIONS ARE PRESENTED FOR THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDELINE).19 5. REFERENCES21 6. ATTACHMENTS: DECISION TREES #1 THROUGH #821

PAGE – 3 ============

© EMEA 2006 3 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Objective of the guideline This guideline is intended to assist to the extent possible, in the establishment of a single set of global specifications for new drug substan ces and new drug products. It provides guidance on the setting and justification of acceptance crit eria and the selection of test procedures for new drug substances of synthetic chemical origin, and new drug products produced from them, which have not been registered previously in the United States, the European Union, or Japan. 1.2 Background A specification is defined as a list of tests, refe rences to analytical procedures, and appropriate acceptance criteria, which are numerical limits, ranges, or other criteria for the tests described. It establishes the set of criteria to which a drug substance or drug product should conform to be considered acceptable for its intended use. “Conformance to specifications” means that the drug substance and / or drug product, when tested according to the listed analytical procedures, will meet the listed acceptance criteria. Specifications are critical quality standards that are proposed and justified by the manufacturer and approved by regulatory authorities as conditions of approval. Specifications are one part of a total control strategy for the drug substance and drug product designed to ensure product quality and consiste ncy. Other parts of this strategy include thorough product characterization during developmen t, upon which specifications are based, and adherence to Good Manufacturing Practices ; e.g., suitable facilities, a validated manufacturing process, validated test procedure, raw material testing, in-process testing, stability testing, etc. Specifications are chosen to confirm the quality of the drug substance and drug product rather than to establish full characterization, and s hould focus on those characteristics found to be useful in ensuring the safety and efficacy of the drug substance and drug product. 1.3 Scope of the guideline The quality of drug substances and drug products is determined by their design, development, in-process controls, GMP controls, and process va lidation, and by specifications applied to them throughout development and manufacture. This guideline addresses specifications, i.e., those tests, procedures, and acceptance criteria wh ich play a major role in assuring the quality of the new drug substance and new drug pr oduct at release and during shelf life. Specifications are an important component of quality assurance, but are not its only component. All of the considerations listed above are necessary to ensure consistent production of drug substances and drug products of high quality. This guideline addresses only the marketing approval of new drug products (including combination products) and, where applicable, ne w drug substances; it does not address drug substances or drug products durin g the clinical research stages of drug development. This guideline may be applicable to synthetic and se mi-synthetic antibiotics and synthetic peptides of low molecular weight; however, it is not suffici ent to adequately describe specifications of higher molecular weight peptides and polypeptides, and biotechnological/biological products. The ICH Guideline Specifications: Test Procedures and Acceptance Criteria for Biotechnological/Biological Products addresses gui deline specifications, tests and procedures for biotechnological/biological products. Radi opharmaceuticals, products of fermentation, oligonucleotides, herbal products and crude produc ts of animal or plant origin are similarly not covered.

PAGE – 4 ============

© EMEA 2006 4 Guidance is provided with regard to acceptance criteria which should be established for all new drug substances and new drug products, i.e. universal acceptance criteria, and those that are considered specific to individual drug substances and / or dosage forms. This guideline should not be considered all encompassing. Ne w analytical technologies, and modifications to existing technology, are continually being de veloped. Such technologies should be used when justified. Dosage forms addressed in this guideline incl ude solid oral dosage forms, liquid oral dosage forms, and parenterals (small and large volume). Th is is not meant to be an all-inclusive list, or to limit the number of dosage forms to which this guideline applies. The dosage forms presented serve as models, which may be app licable to other dosage forms which have not been discussed. The extended application of the concepts in this guideline to other dosage forms, e.g., to inhalation dosage forms (powders, solutions, etc.), to topical formulations (creams, ointments, gels), and to transdermal systems, is encouraged. 2. GENERAL CONCEPTS The following concepts are important in the development and setting of harmonized specifications. They are not universally applicable , but each should be considered in particular circumstances. This guideline presents a brief definition of each concept and an indication of the circumstances under which it may be applicable. Generally, proposals to implement these concepts should be justified by the applicant and approved by the appropriate regulatory authority before being put into effect. 2.1. Periodic or skip testing Periodic or skip testing is the performance of specified tests at release on pre-selected batches and / or at predetermined intervals, rather than on a batch-to-batch basis with the understanding that those batches not being tested still must meet all acceptance criteria established for that product. This represents a less than full schedule of testing and should therefore be justified and presented to and approved by the regulatory authority prior to implementation. This concept may be applicable to, for example, residual solvents and microbiological testing, for solid oral dosage fo rms. It is recognized that only limited data may be available at the time of submission of an application (see section 2.5). This concept should therefore generally be implemented post-approval. When tested, any failure to meet acceptance criteria established for the periodic test should be handled by proper notification of the appropriate regulatory authority(ies). If these data demonstrate a need to restore routine testing, then batch by batch release testing should be reinstated. 2.2. Release vs. shelf-life acceptance criteria The concept of different acceptance criteria for release vs. shelf-life specifications applies to drug products only; it pertains to the establishmen t of more restrictive criteria for the release of a drug product than are applied to the shelf-l ife. Examples where this may be applicable include assay and impurity (degradation product) levels. In Japan and the United States, this concept may only be applicable to in-house criteria, and not to the regulatory release criteria. Thus, in these regions, the regulatory acceptance criteria are the same from release throughout shelf-life; however, an applicant may choose to have tighter in-house limits at the time of release to provide increased assurance to the applicant that the product will remain within the regulatory acceptance criterion throughout its shelf-life. In the European Union there is a regulatory requirement for distinct specifications for release and for shelf-life where different.

PAGE – 5 ============

© EMEA 2006 5 2.3 In-process tests In-process tests, as presented in this guidelin e, are tests which may be performed during the manufacture of either the drug substance or drug product, rather than as part of the formal battery of tests which are conducted prior to release. In-process tests which are only used for the purpos e of adjusting process parameters within an operating range, e.g., hardness and friability of tablet cores which will be coated and individual tablet weights, are no t included in the specification. Certain tests conducted during the manufacturing process, where the acceptance criterion is identical to or tighter than the release requirement, (e.g., pH of a solution) may be sufficient to satisfy specification requirements when the test is included in the specification. However, this approach should be validated to show that test results or product performance characteristics do not change from the in-process stage to finished product. 2.4. Design and development considerations The experience and data accumulated during the development of a new drug substance or product should form the basis for the setting of specifications. It may be possible to propose excluding or replacing certain tests on this basis. Some examples are: • microbiological testing for drug substances and solid dosage forms which have been shown during development not to support microbial viability or growth (see Decision Trees #6 and #8). • extractables from product containers where it has been reproducibly shown that either no extractables are found in the drug product or the levels meet accepted standards for safety. • particle size testing may fall into this category, may be performed as an in-process test, or may be performed as a release test, depending on its relevance to product performance. • dissolution testing for immediate rele ase solid oral drug products made from highly water soluble drug substances may be replaced by disintegration testing, if these products have been demonstrated during development to have consistently rapid drug release characteristics (see Decision Trees #7(1) through #7(2)). 2.5. Limited data available at filing It is recognized that only a limited amount of data may be available at the time of filing, which can influence the process of setting acceptance criteria. As a result it may be necessary to propose revised acceptance criteria as additio nal experience is gained with the manufacture of a particular drug substance or drug product (example: acceptance limits for a specific impurity). The basis for the acceptance criteria at the time of filing should necessarily focus on safety and efficacy. When only limited data are available, the initially approved tests and acceptance criteria should be reviewed as more information is collected, with a view towards possible modification. This could involve loosening, as well as tightening, acceptance criteria as appropriate. 2.6 Parametric release Parametric release can be used as an operational alternative to routine release testing for the drug product in certain cases when approved by th e regulatory authority. Sterility testing for terminally sterilized drug products is one example. In this case, the release of each batch is based on satisfactory results from monitoring spec ific parameters, e.g., temperature, pressure,

PAGE – 6 ============

© EMEA 2006 6 and time during the terminal sterilization phase(s) of drug product manufacturing. These parameters can generally be more accurately controlled and measured, so that they are more reliable in predicting sterility assurance than is end-product sterility testing. Appropriate laboratory tests (e.g., chemical or physical indicator) may be included in the parametric release program. It is important to note that the sterilization process should be adequately validated before parametric release is proposed and maintenance of a validated state should be demonstrated by revalidation at established inte rvals. When parametric release is performed, the attribute which is indirectly controlled (e.g., sterility), together with a reference to the associated test procedure, still shoul d be included in the specifications. 2.7 Alternative procedures Alternative procedures are those which may be used to measure an attribute when such procedures control the quality of the drug subs tance or drug product to an extent that is comparable or superior to the official procedure. Example: for tablets that have been shown not to degrade during manufacture, it may be permissible to use a spectrophotometric procedure for release as opposed to the offici al procedure, which is chromatographic. However, the chromatographic procedure should st ill be used to demonstrate compliance with the acceptance criteria during the shelf-life of the product. 2.8 Pharmacopoeial tests and acceptance criteria References to certain procedures are found in pharmacopoeias in each region. Wherever they are appropriate, pharmacopoeial procedures should be utilized. Whereas differences in pharmacopoeial procedures and/or acceptance criteria have existed among the regions, a harmonized specification is possible only if the procedures and acceptance criteria defined are acceptable to regulatory authorities in all regions. The full utility of this Guideline is dependent on the successful completion of harmonization of pharmacopoeial procedures for several attrib utes commonly considered in the specification for new drug substances or new drug products. The Pharmacopoeial Discussion Group (PDG) of the European Pharmacopoeia, the Ja panese Pharmacopoeia, and the United States Pharmacopeia has expressed a commitment to achi eving harmonization of the procedures in a timely fashion. Where harmonization has been achieved, an appropriate reference to the harmonized procedure and acceptance criteria is consider ed acceptable for a specification in all three regions. For example, after harmonization steril ity data generated using the JP procedure, as well as the JP procedure itself and its acceptance criteria, are considered acceptable for registration in all three regions. To signify th e harmonized status of these procedures, the pharmacopoeias have agreed to include a statem ent in their respective texts which indicates that the procedures and acceptance criteria from all three pharmacopoeias are considered equivalent and are, therefore, interchangeable. Since the overall value of this Guideline is linked to the extent of harmonization of the analytical procedures and acceptance criteria of the pharmacopoeias, it is agreed by the members of the Q6A expert working group that none of the three pharmacopoeias should change a harmonized monograph unilaterally. According to the PDG procedure for the revision of harmonized monographs and chapters , fino pharmacopoeia shall revise unilaterally any monograph or chapter after sign-off or after publication.fl 2.9 Evolving technologies New analytical technologies, and modifications to existing technology, are continually being developed. Such technologies should be used when they are considered to offer additional assurance of quality, or are otherwise justified.

PAGE – 8 ============

© EMEA 2006 8 Test results from stability and scale-up / vali dation batches, with emphasis on the primary stability batches, should be considered in setting and justifying specifications. If multiple manufacturing sites are planned, it may be valuable to consider data from these sites in establishing the initial tests and acceptance criteria. This is particularly true when there is limited initial experience with the manufacture of the drug substance or drug product at any particular site. If data from a single representative manufacturing site are used in setting tests and acceptance criteria, product manufactured at all sites should still comply with these criteria. Presentation of test results in graphic form at may be helpful in justifying individual acceptance criteria, particularly for assay values and impurity levels. Data from development work should be included in such a presentation, along with stability data available for new drug substance or new drug product batches manufactured by the proposed commercial processes. Justification for proposing exclusio n of a test from the specification should be based on development data and on process validation data (where appropriate). 3.2 Universal tests/criteria Implementation of the recommendations in the following section should take into account the ICH Guidelines Text on Validation of Analytical Procedures and Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology . 3.2.1. New drug substances The following tests and acceptance criteria are considered generally applicable to all new drug substances. a) Description : a qualitative statement about the state (e.g. solid, liquid) and color of the new drug substance. If any of these characteristics change during storage, this change should be investigated and appropr iate action taken. b) Identification: identification testing should optimally be able to discriminate between compounds of closely related structure which ar e likely to be present. Identification tests should be specific for the new drug substance, e.g., infrared spectroscopy. Identification solely by a single chromatographic retention ti me, for example, is not regarded as being specific. However, the use of two chromatographic procedures, where the separation is based on different principles or a combination of te sts into a single procedure, such as HPLC/UV diode array, HPLC/MS, or GC/MS is generall y acceptable. If the new drug substance is a salt, identification testing should be specific for th e individual ions. An identification test that is specific for the salt itself should suffice. New drug substances which are optically active may also need specific identification testing or performance of a chiral assay. Please re fer to 3.3.1.d) in this Guideline for further discussion of this topic. c) Assay: A specific, stability-indicating procedure should be included to determine the content of the new drug substance. In many cases it is possible to employ the same procedure (e.g., HPLC) for both assay of the new drug substance and quantitation of impurities. In cases where use of a non-specific assay is ju stified, other supporting analytical procedures should be used to achieve overall specificity. For example, where titration is adopted to assay the drug substance, the combination of the assay and a suitable test for impurities should be used. d) Impurities: Organic and inorganic impurities and residual solvents are included in this category. Refer to the ICH Guidelines Impurities in New Drug Substances and Residual Solvents in Pharmaceuticals for detailed information.

PAGE – 9 ============

© EMEA 2006 9 Decision tree #1 addresses the extrapolation of meaningful limits on impurities from the body of data generated during development. At the time of filing it is unlikely that sufficient data will be available to assess process consistency. Therefore it is considered inappropriate to establish acceptance criteria which tightly encomp ass the batch data at the time of filing. (see section 2.5) 3.2.2. New drug products The following tests and acceptance criteria are considered generally applicable to all new drug products: a) Description: A qualitative description of the dosage form should be provided (e.g., size, shape, and color). If any of these characteristics change during manufacture or storage, this change should be investigated and appropriate action taken. The acceptance criteria should include the final acceptable appearance. If color changes during storage, a quantitative procedure may be appropriate. b) Identification: Identification testing should establish the identity of the new drug substance(s) in the new drug product and should be able to discriminate between compounds of closely related structure which are likely to be present. Identity tests should be specific for the new drug substance, e.g., infrared spectroscopy. Identification solely by a single chromatographic retention time, for example, is not regarded as being specific. However, the use of two chromatographic procedures, where the separation is based on different principles, or combination of tests into a single procedure, such as HPLC/UV diode array, HPLC/MS, or GC/MS, is generally acceptable. c) Assay: A specific, stability-indicating assay to determine strength (content) should be included for all new drug products. In many cases it is possible to employ the same procedure (e.g., HPLC) for both assay of the new drug subs tance and quantitation of impurities. Results of content uniformity testing for new drug products can be used for quantitation of drug product strength, if the methods used for conten t uniformity are also appropriate as assays. In cases where use of a non-specific assay is ju stified, other supporting analytical procedures should be used to achieve overall specificity. For example, where titration is adopted to assay the drug substance for release, the combination of the assay and a suitable test for impurities can be used. A specific procedure should be used when there is evidence of excipient interference with the non-specific assay. d) Impurities: Organic and inorganic impurities (degra dation products) and residual solvents are included in this category. Refer to the ICH Guidelines Impurities in New Drug Products and Residual Solvents for detailed information. Organic impurities arising from degradation of the new drug substance and impurities that arise during the manufacturing process for th e drug product should be monitored in the new drug product. Acceptance limits should be stat ed for individual specified degradation products, which may include both identified and unidentified degradation products as appropriate, and total degradation products. Process impurities from the new drug substance synthesis are normally controlled during drug subs tance testing, and therefore are not included in the total impurities limit. However, when a synthesis impurity is also a degradation product, its level should be monitored and incl uded in the total degradation product limit. When it has been conclusively demonstrated vi a appropriate analytical methodology, that the drug substance does not degrade in the specific formulation, and under the specific storage conditions proposed in the new drug applicati on, degradation product testing may be reduced or eliminated upon approval by the regulatory authorities. Decision tree #2 addresses the extrapolation of meaningful limits on degradation products from the body of data generated during development. At the time of filing it is unlikely that

PAGE – 10 ============

© EMEA 2006 10 sufficient data will be available to assess pr ocess consistency. Therefore it is considered inappropriate to establish acceptance criteria which tightly encompass the batch data at the time of filing. (see section 2.5) 3.3 Specific tests/criteria In addition to the universal tests listed above, th e following tests may be considered on a case by case basis for drug substances and/or drug products. Individual te sts/criteria should be included in the specification when the tests have an impact on the quality of the drug substance and drug product for batch control. Tests other than those listed below may be needed in particular situations or as new information becomes available. 3.3.1. New drug substances a) Physicochemical properties: These are properties such as pH of an aqueous solution, melting point / range, and refractive index. The procedures used for the measurement of these properties are usually unique and do not need mu ch elaboration, e.g., capillary melting point, Abbé refractometry. The tests performed in this category should be determined by the physical nature of the new drug substance and by its intended use. b) Particle size: For some new drug substances intended for use in solid or suspension drug products, particle size can have a significant eff ect on dissolution rates, bioavailability, and / or stability. In such instances, testing for partic le size distribution should be carried out using an appropriate procedure, and accep tance criteria should be provided. Decision tree #3 provides additional guidance on when particle size testing should be considered. c) Polymorphic forms: Some new drug substances exist in different crystalline forms which differ in their physical properties. Polymorphi sm may also include solvation or hydration products (also known as pseudopolymorphs) and amorphous forms. Differences in these forms could, in some cases, affect the qual ity or performance of the new drug products. In cases where differences exist which have been shown to affect drug product performance, bioavailability or stability, then the appropriate solid state should be specified. Physicochemical measurements and techniques are commonly used to determine whether multiple forms exist. Examples of these procedures are: melting point (including hot-stage microscopy), solid state IR, X-ray powder diffract ion, thermal analysis procedures (like DSC, TGA and DTA), Raman spectroscopy, optical microscopy, and solid state NMR. Decision trees #4(1) through 4(3) provide additional guidance on when, and how, polymorphic forms should be monitored and controlled. Note: These decision trees should be followed sequentially. Trees 1 and 2 consider whether polymorphism is exhibited by the drug substance, and whether the different polymorphic forms can affect performance of the drug product. Tree 3 should only be applied when polymorphism has been demonstrated for the drug substance, and shown to affect these properties. Tree 3 considers the potential for change in polymorphic forms in the drug product, and whether such a change has any effect on product performance. It is generally technically very difficult to measure polymorphic changes in drug products. A surrogate test (e.g., dissolution) (see Decision tree 4(3)) can generally be used to monitor product performance, and polymorph content shoul d only be used as a test and acceptance criterion of last resort. d) Tests for chiral new drug substances: Where a new drug substance is predominantly one enantiomer, the opposite enantiomer is excluded from the qualification and identification thresholds given in the ICH Guidelines on Impurities in New Drug Substances and Impurities in New Drug Products because of practical difficulties in quantifying it at those levels.

PAGE – 11 ============

© EMEA 2006 11 However, that impurity in the chiral new drug substance and the resulting new drug product(s) should otherwise be treated according to the principles established in those Guidelines. Decision tree #5 summarizes when and if chiral identity tests, impurity tests, and assays may be needed for both new drug substances and new drug products, according to the following concepts: Drug Substance: Impurities. For chiral drug substances which are developed as a single enantiomer, control of the other enantiomer sh ould be considered in the same manner as for other impurities. However, technical limi tations may preclude the same limits of quantification or qualification from being applie d. Assurance of control also could be given by appropriate testing of a starting material or intermediate, with suitable justification. Assay. An enantioselective determination of the drug substance should be part of the specification. It is considered acceptable for this to be achieved either through use of a chiral assay procedure or by the combination of an achiral assay together with appropriate methods of controlling the enantiomeric impurity. Identity. For a drug substance developed as a single enantiomer, the identity test(s) should be capable of distinguishing both enantiomers and the racemic mixture. For a racemic drug substance, there are generall y two situations where a stereospecific identity test is appropriate for release/accep tance testing: 1) where there is a significant possibility that the enantiomer might be substituted for the racemate, or 2) when there is evidence that preferential crystallization ma y lead to unintentional production of a non- racemic mixture. Drug Product: Degradation products. Control of the other enantiomer in a drug product is considered necessary unless racemization has been shown to be insignificant during manufacture of the dosage form, and on storage. Assay: An achiral assay may be sufficient where racemization has been shown to be insignificant during manufacture of the dosage form, and on storage. Otherwise a chiral assay should be used, or alternatively, the combination of an achiral assay plus a validated procedure to control the presence of the opposite enantiomer may be used. Identity: A stereospecific identity test is not generally needed in the drug product release specification. When racemization is insignificant during manufacture of the dosage form, and on storage, stereospecific identity testing is more appropriately addressed as part of the drug substance spec ification. When racemization in the dosage form is a concern, chiral assay or enantiom eric impurity testing of the drug product will serve to verify identity. e) Water content: This test is important in cases wher e the new drug substance is known to be hygroscopic or degraded by moisture or when the drug substance is known to be a stoichiometric hydrate. The acceptance criteria may be justified with data on the effects of hydration or moisture absorption. In some cases, a Loss on Drying procedure may be considered adequate; however, a detection proc edure that is specific for water (e.g., Karl Fischer titration) is preferred. f) Inorganic impurities: The need for inclusion of tests and acceptance criteria for inorganic impurities (e.g., catalysts) should be studied du ring development and based on knowledge of the manufacturing process. Procedures and acce ptance criteria for sulfated ash / residue on ignition should follow pharmacopoeial preced ents; other inorganic impurities may be determined by other appropriate procedur es, e.g., atomic absorption spectroscopy. g) Microbial limits: There may be a need to specify the total count of aerobic microorganisms, the total count of yeasts and molds, and the absence of specific objectionable

63 KB – 32 Pages