Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”). • Feminist Ethics. Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and.

96 KB – 6 Pages

PAGE – 1 ============

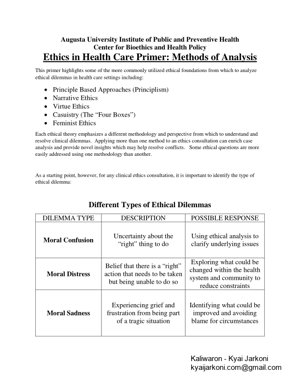

pg. 1 Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer : Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the mo re commonly utilized ethical foundations fr om which to analyz e ethical dilemmas in health care settings including : Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) Narrative Ethics Virtue Ethics Casuistry (The fiFour Boxesfl ) Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a differ ent methodolog y and perspective from which to understand and resolv e clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insight s which may help resolve co nflict s. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one method ology than another. As a starting point , however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemma s DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Moral Confusion Uncertainty about the firight fl thing to do Using ethical analysis to clarify underlying issues Moral Distress Belief that there is a firightfl action that needs to be taken but being unable to do so Explor ing what could be changed within the health system and community to reduce constraints Moral Sadness Experienc ing grief and frustration from being part of a tragic situation Identify ing what could be improved and avoiding blame for circumstances

PAGE – 2 ============

pg. 2 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describe s a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles centra l in the ethical practice of health care 1: 1. Respect for autonomy – Respecting the decision -making capacity of autonomous persons 2. Nonmaleficence – Avoiding causation of harm 3. Beneficence – Providing benefit s and balancing benefit s against risks and costs 4. Justic e- Distributing benefits, risk and cost fairly Beauchamp and Childress apply these four principles to ethical analysis using an iterative process they refer to as coherentism , which they distinguish from traditional deductive and inductive methods of reasoning : fiIn d eductive methods , particular actions are based on rules and principles that are in turn justified by an ethical theory. If one understands the theory, one can determine the appropriate action. Inductive methods assume that moral justi fication proceeds in the opposite direction: existing social agreements and practices serve as the starting point for evaluating a particular situation and determin ing the appropriate course of action. Through the resolution of a series of similar cases, it is possible to derive rules and principles that codify concepts of moral behavior. fl1 Coherentism , by contrast, emphasizes that moral decision -making proceed s in both directions through the practice of reflective equilibrium and that bioethic al principles provide general guidelines which leave considerable room for personal judgement. Applying the four principles to s imilar clinical situations leads to the development of generalizable rules of conduct that guid e coherent normative action s by pro viders . If the application of these principle s to a certain case yields a conclusion that is at odds with reasoned judgment (for example, over emphasi s on personal autonomy and the resulting rule of confidentiality, leads a health care provider to fail to war n a third party about an avoidable harm ), it is appropriate to revisit the principle and ask whether its interpretation is appropriate . 1. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics , 6th edition. Oxford University Press; 2009.

PAGE – 3 ============

pg. 3 Narrative Ethics Narrative ethics uses the nuance s and complexities of stories ( the narrative sequence ), to identify and evaluate ethical dimensions of situation s. These narratives , sometimes presented as case histories , are integral to optimizing ethical discourse and to answering question s raised by particular situation s. As a form of ethical inquiry, narrative analyses enhance the details of situation s being examined , allow ing the deeper moral content of specific situations and choices to be better illuminated .1 Narrative inquires provide a means to: Embody values and principles in action Explore moral justification for actions Appreciate different perspectives and positions Understand the wider context of dilemma s Example s of ethical narrative inquires include : What is unique about this patient™s story which helps to better inform us about the ir understanding of medical benefit and harm? What sequence of events and life circumstances led this patient to seek this medical intervention ? How does the clinician experience caring for this patient? If a patient refuses standard therapy, how did those events unfold from the patient™s and health care provider™s perspectives? If a therapy is controversial, what is the sequence of arguments for and against it? Narrative ethics analysis has been described as having four components 2: 1. Recognition – Identify ing the case and its participants 2. Formulation – Examining the details given and how they were presented 3. Interpretation – Embracing multiple points of view, identify ing metaphors, tolerat ing ambiguity and contradiction , elucidating which information should be trusted versus questioned 4. Validation – Ask ing whether the interpretation of facts and ethical justifications are reasonable and reliable or if they might be incomplete, biased, o r in conflict with major values 1. Murray TH. fiWhat do we mean by narrative ethics? fl Med Human Rev 1997; 11: 44 -57. 2. Charon R. A Matter of Principles? Currents in US Bioethics . Trinity Press 1994.

PAGE – 4 ============

pg. 4 Virtue Ethics Proponents of v irtue ethics believe that good medical practice requires a virtuous health care provider. Central to this claim is the belief that the telos (ultimate aim) of medicine is the good of the patient. With a virtuous temperament, a moral physician strives for the balance between extremes of excess and deficiency, ch oosing actions which promote patient good . According to Pellegrino and Thomasma, t he key virtue for a physician’s character is prudence, which is fiboth a moral and an intellectual virtue that disposes one habitually to choose the right thing to do in a concrete moral situation.fl 1 The virtuous health care provider: Is dedicated to the good of the patient Subsumes personal interests for the patient™s needs Makes the best choice to further the patient™s good and well -being through exercise of prudent judgement. Such judgement is achieved by the provider™s intrinsic character, strengthened by medical trai ning and by habits that foster a disciplined, service oriented profess ional integrity in which the character and virtues of providers are derive d from the needs of patients. How do these concepts translate in ethical analysis? First , virtue ethics asks us to pay attention to the actions and motivations of the clinician What choices are available to the clinician? What are the moral implications of these choices? Why does the clinician propose a particular course of action? What kind of clinician does this person want to be? Second, virtue ethics emphasizes the importance of the patient™s well -being, calling for certain explicit virtues in medical practice, including a personal response to the patient, gentleness, truth -telling, and concern for the patient™s privacy. In addressing the patient™s well -being , the provider is asked to think expansively about the meaning of the figood of the patient.fl Four components, of ascending value , are central to that analysis : The medical good The patient™s perception of the good The good for humans Spiritual good The fundamental question in virtue ethics is what actions, among all those available to the provider, best enable the provider™s core professional responsibility to achieve good? 1. Pellegrino ED and Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice . Oxford University Press, 1993 .

PAGE – 5 ============

pg. 5 Casuistry Casistry is a case-based approach to ethical decision making sharing many features with medical and legal decision making. Appropriate actions depend on the specific features of a case. Following the approach of Jonsen et al., four topics are basic and intrinsic to every clinical encounter: The Four Topics Chart Medical Considerations 1.What is the patient™s medical problem? Is th e problem Acute? Chronic? Critical? Reversible? Emergent? Terminal? 2. What are the goals of treatment? 3. In what circumstances are further medical treatments not indicated? 4. What are the probabilities of success for various treatment options? 5. How can this patient benefit from medical and nursi ngcare? How can harm be avoided? Patient Preferences 1.Has the patient been informed of the risk s and benefits of treatment, understood the information, and given consent? 2. Is the patient mentally cable and legally competent? 3. What treatment preferences has the patient stated? 4. If incapacitated, has the patient expr essed prior preferences? 5. Who is the appropriate surrogate decision maker if th epatient lacks capacity? What standards should govern their decisions? 6.Is the patient unwilling or unable to comply with standar dmedical treatment? If so, why? Quality o f Life 1.What are the prospects, with or without treatment, for areturn to normal life? What physical, mental, and socioeconomic might the patient experience even if treatment succeeds? 2.Could resultant quality of life be undesirable for a patient who cannot make or express their own judgement? 3. What biases might prejudice the medical team™s judgement of a patient™s future quality of life? 4. What ethical issues arise concerning improving or enhancing a patient™s quality of life? 5.Do quality -of-life assessments raise any questions that might contribute to a change of treatment plan, such as forgoing life -sustaining treatment? 6.Are there plans to provide pain relief and provide comfort if a decision is made to forgo life -sustaining interventions? 7. Is medically assisted dying ethically or legally permissible? 8. What is the legal and ethical status of suicide? Contextual Features 1.Are there professional, inter professional, or business interests that might create conflicts of interest in the clinical treatment of patients? 2. Are there parties other than the clinician and patient, such as family members, who have a legitimate interest in clinical decision? 3. What are the limits imposed on patient confidentiality bythe legitimate interests of third parties? 4. Are there financial factors that create conflicts of interest in clinical decisions? 5. Are there problems of allocation of resources that affect clinical decision? 6. Are there religious factors that might influence clin ica ldecisions? 7. What are the legal issues that might affect clinica ldecisions? 8. Are there considerations of clinical research and medical education that affect clinical decisions? 9. Are there considerations of public health and safety that influence clinical decisions? 10. Does institutional aff iliation create conflicts of interest that might influence clinical decisions? *Adopted f rom Clinical Ethics: A Practical Approach to Ethical Decisions in Clinical Medicine , 8th ed. Jonsen, et al. The case analysis proceeds in three steps: 1.Eval uate the facts under each topic and identify t he salient features of the case. 2.Identify relevant paradigm cases ; cases with similar features that have been debated and decide dby the general public and medical and legal communities at a national level. 3.Develop a justified plan of action, drawing on the expert opinion from paradigm cases adapted for the specific features (the context) of that particular case.

PAGE – 6 ============

pg. 6 Feminist Ethics Feminist ethic al perspective s highlight the potential power differentials that may exist between individuals due to professional standing, gender, race, language, disability, etc. which can create barriers in the delivery of safe, effective medical care . Paternalistic provider attitudes are discou raged given th at they arise from an authoritarian framework in which the fiphysician knows bestfl and can result in medical decisions being made for patients in contrast to with patient s™ input. Utilizing a feminist ethics framework, an ethical dilemma can be evaluated through the consideration of four domains: 1) Identifying who is vulnerable Ethical analysis should privilege the most vulnerable as the moral litmus test of a good society is how well it cares for its most vulnerable members. 2) Valuing the knowle dge that comes from experience s Collective and personal experiences add important context to medical decision -making . Embodiment , the connectedness of mind and body, is appreciated. 3) Analyzing the structure in which the dilemma occurs. Do power differences exist? Are viewpoints being suppressed? 4) Considering what justice means in the context of firight -relationshipfl Right -relationships include honoring the dignity of all human beings and affirming relations based on mutuality (as opposed to domi nation) In the context of these domains, some general questions can help to approach an issue from a feminist ethics perspective : What is happening in this situation? In particular, what is happening to those who are vulnerable? Who/wh at is being ignored? Are there questions that are not being asked? Should I be suspicious of the dominant narrative/paradigm? Who benefits? At whose expense?

96 KB – 6 Pages