Romanians, Serbs, and others, were classified as dhimmi (protected subject non-Muslims). The dhimmi were granted considerable religious freedom, but they

357 KB – 199 Pages

PAGE – 3 ============

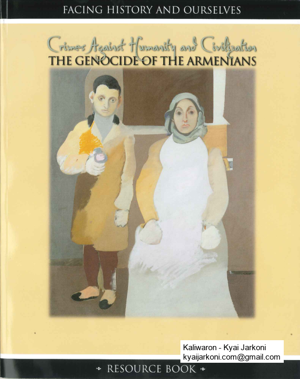

Acknowledgment of photographs and other images accompany the images throughout the book. Acknowledgment of the many documents and other quotations included in this book may be found at the end of each reading. Every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge owners of copyrighted materials, but in some cases that has proved impossible. Facing History and Ourselves would be pleased to add, correct, or revise such citations in future printings. Cover Painting by Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, ca. 1926-1936, courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Jacket and book design by Sandy Smith-Garcés Copyright©2004 by Facing History and Ourselves Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. Facing History and Ourselves®is a trademark registered in the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. Facing History and Ourselves, 16 Hurd Road, Brookline, MA 02445 (617) 232-1595 www.facinghistory.org Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9754125-0-7 II•Facing history and ourselves

PAGE – 4 ============

the genocide of the armenians •IIIThis book is dedicated to Dr. Charles K. and Beverly J. Achki. Among those who have known them, they have set a compelling example of human decency and respect for others that embodies the principles taught in Facing History and Ourselves. Given in their honor by Tom Blumenthal and Lisa Achki Blumenthal and their children.

PAGE – 5 ============

table of contents IV•Facing history and ourselves Chapter 1 identity and history Reading 1 What’s in a Name?Reading 2 Multiple IdentitiesReading 3 Am I Armenian?Reading 4 GenerationsChapter2 We and they Reading 1 The Ottoman ArmeniansReading 2 Iron Ladles for Liberty StewReading 3 Organizing for ChangeReading 4 Humanity on Trial Reading 5 The Sultan RespondsReading 6 Seeking Civil RightsReading 7 Humanitarian Intervention Reading 8 Showdown at Bank OttomanReading 9 The Rise of the Young Turks Chapter 3 the young turks in power Reading 1 Bloody News From AdanaReading 2 IdeologyReading 3 Ideology in ActionReading 4 Neighbor Turns Against Neighbor Reading 5 Planning Mass MurderReading 6 Dictating ReligionChapter 4 genocide Reading 1 Evacuation,Deportation,and DeathReading 2 Under the Cover of War Reading 3 The Round Ups Begin3610 142528 31 35 39 42 45 48 515761 65 68 72 768387 921215581

PAGE – 6 ============

the genocide of the armenians •VReading 4 The German ConnectionReading 5 Following OrdersReading 6 Women and the Deportations Reading 7 Cries Ringing in My EarsReading 8 Targeting the Greeks and the Assyrians Chapter 5 the range of choices Reading 1 Remembering RescueReading 2 Trying to Make a Difference Reading 3 Official PolicyReading 4 Taking a Stand Reading 5 The American Ambassador in ConstantinopleReading 6 Talaat and the Limits of Diplomacy Reading 7 The Eyes of the World Reading 8 Saving the ArmeniansReading 9 Armenian ReliefReading 10 The Story of Aurora Mardiganian and“Ravished Armenia”Chapter 6 Who Remembers the Armenians? Reading 1 A Mandate for Armenia?Reading 2 Crimes Against Humanity and CivilizationReading 3 War ,Genocide,and Human RightsReading 4 The Armenian Republic and the New Turkey Reading 5 Acquitting the AssassinReading 6 Rewriting History Reading 7 The Legacy of aWitness Reading 8 Remembrance and DenialReading 9 Denial,Free Speech,and Hate SpeechReading 10 Demanding JusticeReading 11 Meeting the PastReading12 The Crime of Genocideindex 9498101 104 107115118 121 124 127 131 134 137 139 142149155 159 162 165 167 170 174 177 180 182 184191113147

PAGE – 8 ============

In 1939, just before the invasion of Poland, Adolf Hitler told his generals: The aim of war is not to reach definite lines but to annihilate the enemy physically. It is by this means that we shall obtain the vital living space that we need. Who today still speaks of the massacre of the Armenians?IHe was referring to the systematic murder of the Armenians by Turkish leaders of the Ottoman Empire during World War I. In May 1915, in the midst of the war, Britain, Russia, and France warned that those leaders would be held accountable for “crimes against humanity and civilization” if the massacres con- tinued. The Turks ignored the warning. In July, Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, begged the State Department to take action against what he called the “race murder” of the Armenians. Instead, the nation chose to remain neutral. Henry Sturmer, a journalist for the German newspaper Kolnische Zeitung, was also outraged by the mur-ders. He wanted Germany to use its influence as an ally of the Ottoman Empire to stop the systematic extermination of the Armenians. When they failed to do so, he wrote: The mixture of cowardice, lack of conscience, and lack of foresight of which our government has been guilty in Armenian affairs is quite enough to undermine completely the political loyalty of any think- ing man who has any regard for humanity and civilization. IIHitler learned a lesson from the world’s response to the mass murder of the Armenians. So did many Jews. Michel Mazor, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto, recalled: “During the terrible days of July and August 1942, we often spoke of the fate of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915.” He wondered if “the gas chambers and crematoria of Auschwitz and Treblinka” would have come into being if “at the end of the First World War, a ‘Nuremberg Tribunal’ had convened at Istanbul.” When Raphael Lemkin, a young Polish Jew, learned about the massacre of the Armenians, he asked a law professor why no one had indicted the perpetrators for murder. The professor explained that there was no law under which they could be tried. In 1944, Lemkin coined the word genocideto describe themass murder of a people and wrote a law that would make genocide a crime without borders. After World War II and the founding of the United Nations, it became part of international law. The story of the Armenian Genocide and its legacies is told in Facing History’s newest resource book, Crimes Against Humanity and Civilization: The Genocide of the Armenians. It is a history that is as relevant today as it was in the 1940s. It raises important questions about our own responsibilities as individuals the genocide of the armenians •VIIintroduction

PAGE – 9 ============

and as members of groups and nations to those beyond our borders. These questions have long been central to the work of Facing History and Ourselves. Soon after thefounding of the organization in 1976, Manoog Young of the National Association of Armenian Studies and Research approached us with the idea of creating a study guide on the Armenian Genocide as a com- panion to Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior . He and others in the Armeniancommunity were eager to tell the story of what was then a “forgotten genocide.” The booklet marked the beginning of our work with the history of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Our long association with Richard Hovannisian, professor of Near Eastern Studies at the University of California at Los Angeles and now a member of the Facing History and Ourselves Board of Scholars, heightened our awareness of the genocide and its legacies. At our workshops and institutes, he describes how the failure to bring the perpetrators to justice and Turkey’s evolving denials of the mas- sacre have complicated our understanding of not only genocide but also guilt and responsibility. We could not have produced Crimes Against Humanity and Civilization: The Genocide of the Armenianswithout the support of Richard Hovannisian. We are deeply appreciative of his friendship, aid, and assis- tance. We are also grateful to Carol Mugar for the grant to this project that funded our research, and to scholars Peter Balakian and Henry Theriault for their guidance and advice in creating this valuable resource. Special thanks to Thomas and Lisa Blumenthal, whose generous grant supports the printing of the book and its dissemination to educators. Facing History and Ourselves would also like to acknowl- edge the efforts of Senior Program Associate Mary Johnson in creating the first drafts of the book; Adam Strom who researched, wrote, and edited the final manuscript; Marc Skvirsky and Margot Stern Strom for their leadership; Sandy Smith-Garcés who designed the book; Chris Stokes and Cynthia Platt for helping to turn this manuscript into a book, as well as Karen Lempert, Sarah Gray, Melinda Jones- Rhoades, and Tracy O’Brien for their work in the library overseeing permissions requests. VIII•Facing history and ourselves I. Samantha Power, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 2002), p. 23. II. Deborah Dwork and Robert Jan van Pelt, The Holocaust: A History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2002), pp. 39–40. notes

PAGE – 10 ============

WE BEGIN TO LEARN OUR CULTURE—THE WAYS OF OUR SOCIETY—JUST AFTER BIRTH. THIS PROCESS IS CALLED socialization, and it involves far more than schooling. It influences our values—what we consider right and wrong. Our religious beliefs are an integral part of our culture, as is our racial and ethnic heritage. Our culture shapes the way we work and play, and it makes a difference in the way we view ourselves and others. Psychologist Deborah Tannen warns of our tendency to generalize about the things we observe and the people we encounter. “Generalizations, while capturing similarities, obscure differences. Everyone is shaped by innumerable influences such as ethnicity, religion, race, age, profession, the geo- graphical regions they and their relatives have lived in, and many other group identities—all mingled with personality and predilection.” 1The readings in this chapter address questions about how people come to understand their place in the world. The questions are raised through the stories of individual Armenians. As you read their stories and hear their questions, you will come to see that many of their challenges are familiar to all of us. These read- ings ask: What factors influence how we see ourselves? How can we keep our individuality and still be part of a group? What role does group and family history play in shaping the way we see ourselves and the way others see us? And, finally, how do all of these facets of identity influence the choices that people make. Chapter 1 Identity and History Do you think of yourself as an Armenian?Or an American?Or hyphenated American?—D.M. Thomas“”

PAGE – 11 ============

Today most Armenians do not live in the Republic of Armenia. Indeed, most Armenians have deep ties to the countries where they live. Like a lot of us, many Armenians find them- selves balancing their role in their new country with their historical and cultural roots. How far should they assimilate into their new countries? Does Armenian history and culture have some- thing to offer Armenians as they live their lives now? When do historical and cultural memories create self-imposed limits on individuals? This chapter also explores the way identity passes down from one generation to another. These issues are especially important for a group that lives with the memory of a geno- cide in which over a million and a half Armenians were systematically murdered between 1915 and 1923 in what is now Turkey. The deliberate historical revision, denial of the genocide, and the politicization of traumatic memory have consequences for the generations that live in the shadow of thathistory. Psychologist Ervin Staub, author of The Roots of Evil, observes that we can all learn about ourselves from the way Armenians have responded. He writes: The intense need of the Armenians as individuals and as a community to have the genocide beacknowledged and known by the world teaches us something about ourselves as human beings. First, our identities are rooted not only in our group, but in the history of our group. For a complete iden- tity, we must be integrated not only with our individual past, but also with our groups’ past. Perhaps, this becomes especially important when our group is partly destroyed and dispersed; our families and ourselves have been deeply affected; and in a physical sense we have at best fragments of our group. Second, we have a profound need for our pain and suffering, especially when it is born of injustice, to be acknowledged, known and respected.” 22•Facing history and ourselves An Armenian family, Ordu, Ottoman Empire, c. 1905. Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, Inc., Courtesy of Jack Chitjian, boy on right.

357 KB – 199 Pages